The northern boundary of the Cumberland coalfield was long considered to extend in a sandstone stratum from the north side of Maryport harbour; before running inland along the high ground almost parallel to the Maryport and Carlisle railway line; until close to Aspatria, where the fault was deemed to veer in a southerly direction before skirting round the coal at Harriston. Joseph Harris had contrary beliefs. He proved his theories by driving a drift through the workings of No 3 pit in a northerly direction, before sinking a bore hole from the surface to connect with it. The discovery of coal in this locality left the owner with a difficult dilemma; was this really a genuine fault or was it the one explored at great expense and little success at Crosby and Rosegill some years prior. Harris pondered the problem then sunk his No 4 pit smack in the centre of an extensive reserve of coal.

The site was situated a few hundred yards to the east of Brayton station on land belonging to Sir Wilfrid Lawson and on a royalty owned by the Earl of Egremont. Although it was close to a mere and presented the construction crew with a damp environment; it was geographically well placed, being close to the main Carlisle to Workington road and midway between the ports of Maryport and Silloth (via the Solway Junction Railway).

Work began in 1888, and during the boring operations a total of eight seams were discovered. The first, at a depth of 38 fathoms was sixteen inches high and as hard as slate. Two fathoms deeper they reached the Ten Quarter seam, comprising a mixture of inferior coal and metal. A fourteen-inch seam was discovered at a depth of 52 fathoms. A thirty-inch seam known as the “Cannel” Band at 60 fathoms; the thirteen inch “Metal” band at 65 fathoms; an eight inch seam at 80 fathoms; and between there and the Yard Band at 92 fathoms they recorded a shallow seam. The thickness of the “Yard” seam was 4ft 2ins, but as there was a parting of shale a few inches from the bottom the net thickness was 3ft 9ins. Although the exact extent of the coal in the north-easterly direction was undetermined the seam had favourable characteristics. The roof was ideal, composed of hard blue metal, underlain with slices of freestone, and the floor was even and firm. Instead of rising eastwardly as was invariably the case in the Cumberland coalfields, these seams climbed north at the appropriate rate of three inches to the yard. The product was of the highest quality for household consumption and in consequence demanded a high rate in the market place.

The sinking of the shaft to a depth of 562 feet met all the provisions demanded by the 1887 miners Regulation Act. The sinking machinery (the Jack Roller), the headgear, the winding engine, the engine house and the permanent chimney were all installed in the initial stages. Work progressed satisfactorily until they encountered the stone head in the smaller upcast shaft where the influx of water overcame the capacity of the pump and work was suspended. The upcast shaft, not to be confused with the main shaft, is the shaft that allows the air to return to the surface having ventilated the workings. The owner erected a second pump but the water continued to ooze from the sandstone. In the interim period, they commenced the sinking of the main shaft but at 22 fathoms they were again overwhelmed by water. In the meantime, a third pump was installed and with all three running simultaneously work resumed and eventually progressed to a satisfactory conclusion. The amount of gas given off by both the strata and the smaller seam of coal were enormous and as a safety precaution all of the feeders were recorded.

When completed the diameter inside the masonry of the main shaft was thirteen feet, while the upcast shaft measured ten. Although the distance from the surface was 92 fathoms, the upcast shaft was sunk a few fathoms deeper to communicate with the water lodge. The coal hewn by the men digging this relief was drawn up the shaft in kebbles prior to the erection of the cage.

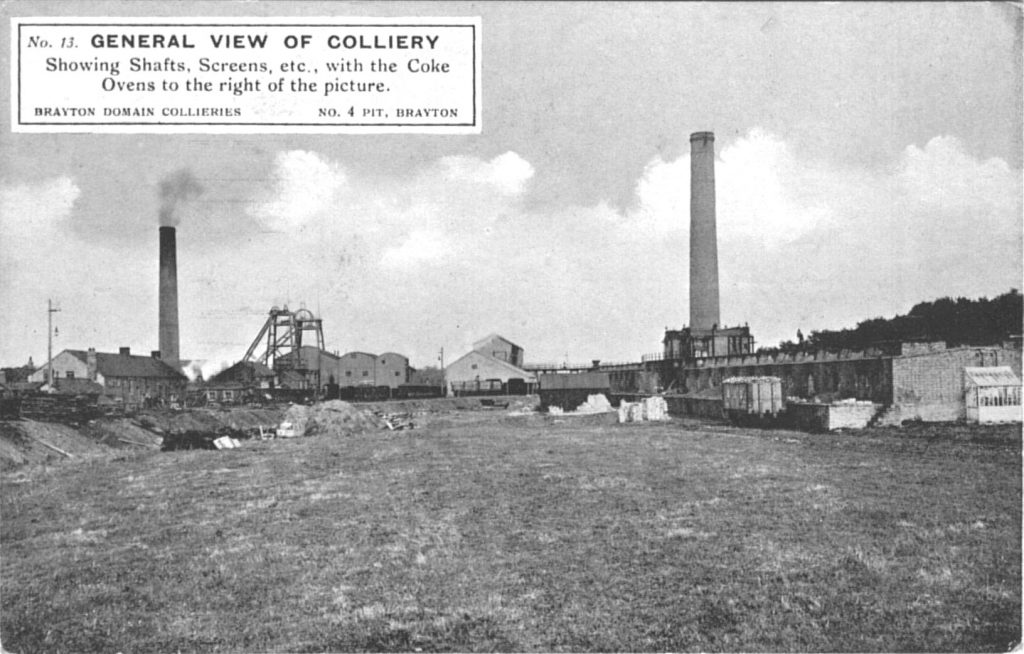

The main shaft was lined with fire clay blocks manufactured at the Birkby and Aiglegill Brickworks, while the archway was constructed from bricks produced at Dearham Colliery. The cages were designed to run on wire slides, with the capacity to lift four tubs at any one time. The screens were designed on the jigger principle and were worked by an engine previously sited at the Ellenborough Colliery. The remainder of the machinery was new and of modern design.

The estimated output at the time of the exploration was 600 tons from a single shift working. However, following the closure of Harriston a double shift system commenced, and output rose to over 1,000 tons. More importantly the work was consistent, the mine worked as regularly in winter as summer; holding the record amongst its contemporaries for the least number of days lost. The mine, often referred to as Wellington Pit because of its proximity to the farm bearing that name, was lit by electricity in 1898. In 1891, over 60 houses were erected on Brayton Road and at Newtown, now called Lawson Street, to accommodate the influx of workers.

The opening of the colliery was celebrated in spectacular style on September 14th 1892. Seventy five workmen were invited to Wellington Farm, where Mr and Mrs Thompson, provided a substantial dinner. The meeting being chaired by Johnathon Bouch, the sole survivor of a group of gentlemen who had performed a similar ceremony after cutting the first sod at No 1 pit, fifty years earlier.

| Previous – Early Days | Next – |

This content of this webpage is the copyright of Terry Carrick – © Terry Carrick 1996 & 2025. All rights reserved. Any redistribution or reproduction of part or all of the contents in any form is prohibited.